Biographies - Biography of Dr. Eugene Botkin

by Patricia A. Scott

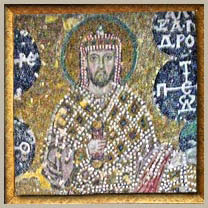

Dr. Eugene Botkin

(1865-1918)Early Life

It is hard to imagine a physician who took the Hippocratic Oath more seriously than Dr. Eugene (Evgeny Sergeivich) Botkin, physician to the last Tsar. His devotion to Nicholas, Alexandra and their children cost him his marriage and eventually his life. Despite his enormous sacrifice, little has been written about him. Anyone acquainted with the facts of his life and the details of his service to the Imperial family must consider his efforts heroic.Dr. Botkin was born in St. Petersburg, Russia in 1865. His father, Dr. Sergei Petrovich Botkin (1832-1889), who served as physician to both Alexander II and Alexander III, is considered the father of Russian medicine. The elder Botkin introduced the practices of triage and post-mortem examination to Russian medicine and created the country’s first experimental medical laboratory. In 1872, he helped to organize Russia’s first medical courses for women. He established St. Petersburg’s system of Duma doctors, a group of physicians paid by the government to provide medical care for the city’s poor, and also set up a system for school sanitary control. As a professor at the Medical Surgical Academy, his students included many who would become prominent scientists, including Nobel Prize winner Ivan Pavlov. He was instrumental in founding the Alexandrovskaya Barracks Hospital for Infectious Disease, later renamed the Botkin Hospital for Infectious Diseases in his honor. S.P. Botkin authored more than seventy-five papers on various aspects of medicine. His published lectures appear in his Clinical Course of Internal Medicine. St. Petersburg: Imperial Academy of Sciences, 1976.

Dr. Eugene Botkin’s brother, Peter Sergeivich, who served as Russian Minister Plenipotentiary in Lisbon, described him as a “studious and conscientious“ child who had “a horror of any kind of struggle or fight” (King 61). As a young man Botkin was a liberal and a free-thinker, though his beliefs stemmed from his innate idealism rather than from any radical political beliefs. While studying at the Academy of Medicine, he suffered temporary expulsion for his spirited defense of fellow students who had run afoul of the college administration. As one of five elders elected by his class, he sent a petition to Alexander III defending the students. Although the Tsar was moved by the sentiments expressed, he could not grant a petition from students and the elders were expelled. It was not uncommon for ‘trouble makers’ from good families who could not be openly arrested to simply disappear at the hands of the secret police. S.P. Botkin knew that even his prominent status as physician to Alexander III could not guarantee his son’s safety. He urged Eugene to maintain a low profile and to avoid going out alone at night. The five young men met for dinner on the day of their expulsion and vowed to meet annually on that date. All five were soon readmitted to the Academy. True to their word, the elders met every year to dine together and have a group portrait taken. If a member was deceased, the others would include a photograph of him in the group portrait. Botkin attended every gathering from 1889 through 1916.

Upon graduation from the Academy of Medicine in 1889, Dr. Botkin was offered the post of physician to Tsarevich George Alexandrovich, which he declined, preferring to continue his studies in Berlin and Heidelberg. His brushes with authority during his student days probably made a position at court seem unappealing. After returning to Russia, Botkin lived in near poverty. At that time it was difficult for physicians to make a decent living in Russia since they were not permitted to bill patients for services but were expected to care for anyone requiring medical treatment regardless of the patient’s ability to pay. Later he became a lecturer at the Academy of Medicine and was appointed chief physician at St. George’s Hospital, positions which provided a modest income for his wife Olga and for their children Dmitri, George, Tatiana and Gleb. During the Russo-Japanese war of 1904-1905, Dr. Botkin served as a volunteer at the front aboard the St. George’s Hospital train. He was later awarded the Grand Cordon of the Order of St. Anne for his distinguished war time service and appointed Chief Commissioner of the Russian Red Cross.

Life at Court

In 1907, Dr. Hirsch, Tsarina Alexandra’s personal physician, died. In 1908, Dr. Botkin was appointed to fill the vacancy. Anna Vyrubova, Alexandra’s friend and confidante, who was sent to convey to Botkin the news of his appointment, reported that “he received the news with astonishment almost amounting to dismay” (Vyrubova). Having grown up the son of a court physician, he realized how demanding the job would be. Age had made him more conservative and more religious, traits which allowed him to adapt to life at court. While he must have been flattered by the Tsar’s confidence in him, he felt “a great burden, a responsibility towards not only the family, but the whole country“ (King 61). Until 1917, the grand duchesses were generally cared for by the pediatrician Dr. Ostrogorsky; Tsarevich Alexi was seen by Dr. Vladimir Derevenko, who was hired by Botkin as an assistant. His calm and personable manner made Dr. Botkin the perfect physician for the Tsarina, who had definite ideas about her ailments and did not like to be contradicted. Her symptoms convinced Alexandra that she had a heart condition, although Botkin believed her symptoms were due to a ‘nervous condition’ brought on by stress and anxiety. He immediately curtailed many of the Tsarina’s activities, advising that long rest periods punctuate her day and that she use a wheelchair when accompanying her children on extended walks. He usually visited her twice daily at 9 a.m. and again at 5 p.m. Botkin often conversed with Alexandra in her native German and due to his fluency in foreign languages, he sometimes served as an interpreter when she received foreign dignitaries.Members of the imperial family and most members of their household liked and respected Dr. Botkin. The imperial children were especially fond of him and made him an unwitting partner in one of their games: “A tall stout man who wore blue suits with a gold watch chain across his stomach, he exuded a strong perfume imported from Paris. When they were free, the young Grand Duchesses liked to track him from room to room, following his trail by sniffing his scent” (Massie 126). Lili Dehn, lady-in-waiting to Alexandra, described him as ”a clever, liberal-minded man” whose “political views were opposed to those of the Imperialists” but whose devotion to the Tsar made these differences seem unimportant (Dehn). Botkin soon found that the plots, intrigues, and malicious gossip of court life were foreign to him. In a letter to his brother written in the autumn of 1909, he vented his frustration: “You would need to have a mind as perverted as theirs and a disordered soul to defeat all of their unbelievable plots. I have decided I am old enough to dare to be myself. I will do the things which I believe to be right and am ready to stand up and defend my actions because they are really my own, and have not been forced upon me” (Zeepvat 157).

Some courtiers believed that Dr. Botkin told Alexandra only what she wanted to hear and that he coddled her, thereby enabling her to avoid her official duties. Others distrusted him because he was on friendly terms with Anna Vyrubova, although their relationship rapidly deteriorated when he refused to befriend Rasputin. Gleb Botkin reported that Rasputin once sought his father’s medical advice on some pretext. After examining Rasputin, Dr. Botkin told him he was perfectly healthy and to avoid calling on him again. From that day on, whenever the two met, “each man turned away his head pretending not to see the other” (Botkin 59).

Dr. Botkin’s days were devoted to the care of the imperial family. At night, he kept up with his students from the Academy of Medicine, fulfilled his obligations to the medical societies to which he belonged and pursued his philanthropic interests. The demands of his position and the devotion with which he performed his duties eventually cost him his marriage. His wife and children accompanied him on the imperial trip to the Crimea in the fall of 1909, but Olga saw so little of him that she left after three weeks. In 1910, she had an affair with their children’s German tutor, Friederich Lichinger, whom she later married. Botkin reluctantly agreed to a divorce and retained custody of their children (Zeepvat 157). Olga died in Berlin during the collapse of the Third Reich.

On September 1, 1911, Dr. Botkin accompanied the imperial family to Kiev for the dedication of a statue in honor of Tsar Alexander III. He was present at the performance of Rimsky-Korsakov’s Tsar Sultan at the Kiev Opera where Prime Minister Peter Stolypin was shot by a terrorist as he and Botkin conversed during the intermission. Botkin was with Stolypin when he died four days later. Gleb and his sister Tatiana met the Tsarevich and young grand duchesses for the first time in person at Livadia that fall and were often invited to the palace to play. Until that time, the Botkin children and the imperial children communicated through Dr. Botkin who carried messages and presents back and forth between the Botkin home and the Alexander Palace. It was at Livadia that the imperial children were introduced to Gleb’s stories and drawings about an imaginary planet of toy animals led by a tsar bear. Years later during their Siberian exile, Gleb continued to amuse the imperial children with these stories. (See: Lost Tales: Stories for the Tsar’s Children. Villiard, 1996.]

In the fall of 1912, Dr. Botkin witnessed one of Rasputin’s ‘miracles.’ Botkin accompanied the Tsar’s family on a hunting trip in Bialowieza, Poland where he cared for Alexi after the child injured his leg jumping out of a boat. A week of bed rest appeared to cure the pain and swelling, so the family moved on to their hunting Lodge at Spala. Soon internal hemorrhaging began with pain and swelling so severe that Drs. Ostrogorsky and Derevenko were summoned along with surgeons Rauchfuss and Fedorov. For several days it seemed that Alexi might die. In desperation Alexandra sent a telegram to Rasputin asking for his prayers and Rasputin replied that Alexis would not die. The next day, the Tsarevich began to recover. None of the physicians involved could give a medical explanation for the sudden reversal of the child’s condition. The year 1913, marked the three-hundredth anniversary of the Romanov dynasty, a celebration which required Dr. Botkin to accompany the imperial family on their travels throughout Russia. The tercentenary observance was the last great national event before World War I. The year of festivities was marred by the illness of Grand Duchess Tatiana, who got typhoid from drinking orangeade prepared with infected water. During the course of her treatment, Dr. Botkin also contracted the disease and was critically ill for several weeks. Nicholas and Alexandra were supportive at first but became impatient with his long convalescence, which included a trip abroad.

Revolution & Exile

The outbreak of World War I in August of 1914 found all of the Botkins involved in the war effort. The Tsarina sent Dr. Botkin to Yalta and Livadia to establish hospitals, his elder sons Dmitri and George were at the front, and Tatiana volunteered as a nurse at the Catherine Palace hospital. That December, Dmitri, a lieutenant in the Cossack regiment on the eastern front, was killed in action. Gleb attributed his father’s increasing fatalism to the death of Dmitri. Dr. Botkin became increasingly spiritual and developed an “abhorrence of the flesh” (Botkin 10). A physician who abhors the flesh presents an interesting contradiction. The carnage Dr. Botkin witnessed, the sheer number and severity of injuries, including the devastating injuries suffered by his son George, must have sometimes made the efforts of contemporary medicine seem useless. Dr. Botkin never faltered in his commitment to relieve physical suffering but after 1914, he lived an increasingly spiritual life and concerned himself with the health of his patients’ souls as well as that of their bodies. It was his spiritual commitment which gave him the strength to endure exile. George, a volunteer with the Fourth Rifles of the Imperial Family, was seriously wounded but survived the war. He was imprisoned and shot by the Nazis during World War II. The patriotic fervor felt by Russians at the beginning of the war dissipated as losses mounted and hatred for Nicholas, Alexandra and Rasputin grew. The murder of Rasputin in December 1916 was a cause of celebration for many courtiers, though Botkin believed it would only make a bad situation worse. When the revolution broke out in St. Petersburg in March of 1917, the Provisional Government placed the Tsarina and her children under house arrest. Alexandra was nursing four of her five children through measles. Only Marie was spared, although she would later contract pneumonia. Convinced that Alexandra needed him more than ever, Dr. Botkin took Gleb and Tatiana to stay at the home of Madame Teviashova, the grandmother of their friends Nicholas and Michael Ushakov, both of whom were at the front. Gleb was able to visit his father in the guard house of the Alexander Palace and wrote to him every day. Botkin helped Alexandra through the abdication of Nicholas on March 15, and the Tsar’s return to Tsarskoe Selo on March 22. He lived under house arrest at the Alexander Palace with the Imperial family from March until August accompanying the family and their servants into exile at Tobolsk in north western Siberia. Gleb and Tatiana were allowed to accompany their father and all three lived together in two rooms of Kornilov House across the street from the former Governor’s Mansion where the Imperial family was confined.

Dr. Botkin unsuccessfully attempted to convince Alexander Kerensky, President of the Provisional Government, that instead of Siberian exile, Alexandra and her children should be sent to the Crimea for health reasons. In Tobolsk he argued for better food and more comfortable conditions for the prisoners, and complained to the Commandant about the rude treatment the family received from their guards. His request that the family be permitted to spend one hour a day walking in the garden was granted, but permission was refused for Alexandra and Alexi to sit on the balcony when they were too ill to walk. Even gaining permission for the family to open a window during the sweltering summer evenings was a battle. The Imperial servants were permitted to go for walks in town but forbidden to enter the homes of private citizens. Dr. Botkin and Dr. Derevenko were the exceptions since the shortage of doctors meant that their services were needed by local residents. Despite the many hardships, Botkin reconciled himself to exile and remained hopeful that the war could still be won and that conditions would improve for the Imperial family. The fact that he was able to continue his work as a physician and had his children near him made exile easier for him to bear. Some members of the Imperial household felt that he adjusted to life in Tobolsk too easily and thought him disloyal for doing so.

Nicholas, Alexandra and members of their retinue divided up responsibility for the children’s education. Dr. Botkin tutored them in Russian. During this period Gleb continued to create stories and drawings for the Imperial children about his toy animals and added to the plot the story of a revolution and a monarch’s struggle to regain his throne. Dr. Botkin acted as the courier, delivering the stories then later relaying the children’s comments and suggestions.

Exile prevented Dr. Botkin from attending the Academy of Medicine’s annual student elders’ reunion in 1917, so the two other remaining elders were photographed with pictures of Dr. Botkin and the deceased members on the table between them. Upon seeing the photograph, he remarked to his son Gleb, “How strange! Am I already dead?” (Botkin 55)

On April 26, 1918, Dr. Botkin left Tobolsk with Nicholas, Alexandra, Grand Duchess Marie and other members of the household. Believing they were bound for England via Moscow, Botkin left a letter for his children assuring them that they would join him in England. Commissar Yaklov told them that Nicholas would be tried in Moscow and sentenced to deportation along with his family. The others stayed behind with Alexis who was recovering from a fall and was too ill to travel. When the party arrived in Tiumen on April 29, Botkin was suffering from liver colic brought on by many hours of travel over bad roads.

On May 3, 1918, Gleb received a letter from his father stating that because train routes to Moscow were blocked by the Bolsheviks, the Imperial household had been sent to live at the Ipatiev House in Ekaterinburg. Upon arrival at the Ekaterinburg train station, Pierre Gilliard, Sophie Buxhoeveden, and Sidney Gibbes were denied permission to accompany the family and were sent back to Tiumen. Forbidden to accompany their father to Ekaterinburg, Gleb and Tatiana moved first to furnished rooms, then to the home of a former District Attorney in Tobolsk. Gleb received two letters from his father cautiously describing the conditions at Ipatiev House, letters described by Gleb as “truly tragic in content and tone” (Botkin 210). During the seventy-eight days of confinement in Ipatiev House, Dr. Botkin often spent evenings with Nicholas and Alexandra. They passed the time together talking, playing cards and listening to Nicholas read aloud. After the execution of Clementi Nagorny, the sailor who had been Alexi’s constant companion, Botkin often spent the night sleeping in Alexi’s room. On June 23, Dr. Botkin suffered a recurrence of colic severe enough to require a morphine injection and was ill for five days. Alexandra sat with him for much of that time (Massie 288).

Death

In the early morning hours of July 17, 1918, Botkin was awakened by Commandant Yurovsky and told to inform the prisoners that the White Army was approaching and that they must be moved to the basement for their own protection. Forty minutes later, Dr. Botkin was murdered by a firing squad along with the Imperial family and the remaining members of their household. Botkin was shot twice in the abdomen; one bullet hit his lumbar vertebrae and the other his pelvis. A third bullet hit his legs breaking his kneecaps and legs. He was also shot in the forehead (King 411). Later, White Army investigators found the following unfinished letter, which Dr. Botkin had begun writing to his brother Alexander:I am making a last attempt at writing a real letter -- at least from here -- although that qualification, I believe, is utterly superfluous. I do not think that I was fated at any time to write to anyone from anywhere. My voluntary confinement here is restricted less by time than by my earthly existence. In essence I am dead -- dead for my children -- dead for my work ... I am dead but not yet buried, or buried alive -- whichever, the consequences are nearly identical ... The day before yesterday, as I was calmly reading ... I saw a reduced vision of my son Yuri's [George’s] face, but dead, in a horizontal position, his eyes closed. Yesterday, at the same reading, I suddenly heard a word that sounded like Papulya. I nearly burst into sobs. Again -- this is not a hallucination because the word was pronounced, the voice was similar, and I did not doubt for an instant that my daughter, who was supposed to be in Tobolsk, was talking to me ... I will probably never hear that voice so dear or feel that touch so dear with which my little children so spoiled me ... If faith without works is dead, then deeds can live without faith [and if some of us have deeds and faith together, that is only by the special grace of God. I became one of these lucky ones through a heavy burden-the loss of my first born, six-month old Serzhi*] ... This vindicates my last decision ... when I unhesitatingly orphaned my own children in order to carry out my physician's duty to the end, as Abraham did not hesitate at God's demand to sacrifice his only son (Kurth 194).*Translation in brackets is mine.

During July and August, there were rumors that the tsar and his family had been executed and other rumors that the family had escaped to Denmark. In an effort to learn the truth, Gleb hopped aboard a munitions train bound for Ekaterinburg. Upon arrival, he met his father’s former assistant Dr. Derevenko, who was living and practicing medicine there. Gleb went to the Ipatiev House but remembering what Derevenko had said about the condition of the bloody and bullet-riddled basement, could not bring himself to enter and returned to Tobolsk. In February of 1919, Gleb was forced to abandon any hope of his father’s survival. He received a letter from Dr. Derevenko in which he explained that “there is no longer any possibility to entertain the slightest hope. We must admit that your father and the whole Imperial family were killed on the night of July 17, 1918, in the cellar of the Ipatieff house” (Botkin 227).

Tatiana married Constantine Melnik, an officer in the Ukrainian Rifles and a long-time family friend, in the fall of 1918. They escaped via Vladivostok, where their daughter Tatiana was born, and later settled in France. Tatiana Botkina Melnik died in Paris in 1986. Gleb escaped to Japan in 1920 and married Nadine Konshin Mandragy, the widowed daughter of the former President of the Russian State Bank. Together with their son, Eugene, the family immigrated to New York in 1922. Gleb worked as an author and illustrator and later founded his own nature-based church called the Church of Aphrodite. He died in Charlottesville, Virginia in 1969. Both Gleb and Tatiana believed Anna Anderson’s claim that she was the Grand Duchess Anastasia and championed her cause throughout their lives.

A set of upper dentures found at the Four Brothers mine in 1918, and a skull exhumed from the mass grave in Koptyaki Forest in 1991, helped to confirm the identity of Dr. Botkin. DNA given by Gleb Botkin’s daughter, Marina Botkina Schweitzer, was also used to identify Dr. Botkin’s remains. In 1981, along with Nicholas, Alexandra, their children and servants, Dr. Botkin was canonized a martyr by the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia. On July 17, 1998, the eightieth anniversaries of his death, Dr. Botkin’s remains were buried with those of the Imperial family and their servants in the Catherine Chapel in the cathedral of the Fortress of St. Peter & St. Paul. His granddaughter, Marina Botkina Schweitzer, attended the funeral with her son Constantine. Along with the Imperial family and those who were murdered with them, Dr. Botkin was canonized a ‘passion bearer’ (i.e., one who met death with Christian humility) by the Russian Orthodox Church on August 19-20, 2000, at the Cathedral of Christ the Savior in Moscow.

Works Cited

Botkin, G. (1931). The Real Romanovs as revealed by the late czar's physician and his

son. New York, NY: Fleming H. Revell Company.

Botkine, T. (1993). Vospominaniia o tsarksoi sem’e i ee zhizni do i posle revoliutsii. Mosvka: Ankor.

Dehn, L. (1922). The Real Tsaritsa. Alexander Palace Time Machine. Retrieved August 26, 2007, from http://www.alexanderpalace.org/realtsaritsa/1chap4.html.

King, G., & Wilson, P. (2003). The fate of the Romanovs. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Kurth, P. (1995). Tsar: the lost world of Nicholas & Alexandra. Boston: Little, Brown and Co.

Massie, R. K. (1967). Nicholas and Alexandra. New York, NY: Atheneum.

Vyrubova, A. (1923?) Memories of the Russian court. Alexander Palace Time Machine. Retrieved August 26, 2007, from http://www.alexanderpalace.org/russiancourt2006/IV.html.

Zeepvat, C. (2000). Romanov autumn, stories from the last century of imperial Russia.

Thrupp, UK: Sutton Publishing.

Imperial Bedroom

Imperial Bedroom Portrait Hall

Portrait Hall Mauve Room

Mauve Room Maple Room

Maple Room Aleksey's Bedroom

Aleksey's Bedroom Nicholas's Study

Nicholas's Study Aleksey's Playroom

Aleksey's Playroom Formal Reception

Formal Reception Balcony View

Balcony View Aleksey- Balcony

Aleksey- Balcony Children-Mauve

Children-Mauve Nicholas's Bathroom

Nicholas's Bathroom Alexandra- Mauve

Alexandra- Mauve Nicholas's Reception

Nicholas's Reception Tsarskoe Selo Map

Tsarskoe Selo Map