The Coronation of the Emperor Nicholas II - The receptions given at Arkhangelskoye and our House in Moscow - Marie, Crown Princess of Rumania - Prince Gritzko.

IN 1896, when the Emperor Nicholas II came to the throne, we went to Arkhangelskoye early in May to entertain the numerous guests who came to take part in the coronation festivities. Among these were the Crown Prince of Rumania and his wife, Princess Marie. In their honor, my parents sent for a Rumanian orchestra which was then very fashionable in Moscow. One of the musicians was a certain Stefanesco, a remarkable cymbal player, who later became one of my intimate friends. He often came with me on my travels. I was extremely fond of listening to him play, which he often did for me alone the whole night through.

The Grand Duke Serge and the Grand Duchess Elisabeth had also invited a number of friends and relations to Elinskoie, their estate, which was only about three miles away from ours. So they were often present at the receptions at Arkhangelskoye. The Emperor and Empress also came to these receptions, which were almost as magnificent as the court balls.

For these festivities we opened our private theater. My parents sent to St. Petersburg for the Italian Opera, with Mazzini, Madame Arnoldson and the corps de ballet. One evening, a few moments before the curtain went up on Faust, my mother was told that Mme. Arnoldson refused to sing because, in the garden scene, the parterres were filled with real flowers and their scent made her feel ill. The flowers bad to be replaced by shrubs before she would go on. I shall never forget another performance at our theater: all the guests were seated in boxes, the stalls were removed, and in their place was a garden of tea roses whose fragrance filled the air.

Above: The Terrace at Arkhangelskoye.

After the performance everyone met on the terrace, where supper was served at tables lighted by tall candelabra. This was followed by a marvelous display of fireworks, an enchanting sight so dazzling to me as a small boy that I hoped I would never be sent to bed.

My parents and their guests went to Moscow a few days before the coronation to take part in another round of fetes. Our house in Moscow originally a sort of super bunting lodge belonging to Ivan the Terrible, had retained its sixteenth-century character; great vaulted halls, medieval furniture, richly wrought gold and silver plate. All this oriental splendor was a wonderful setting for the receptions given by my parents. Foreign princes who had been to them declared that they bad never seen anything like them.

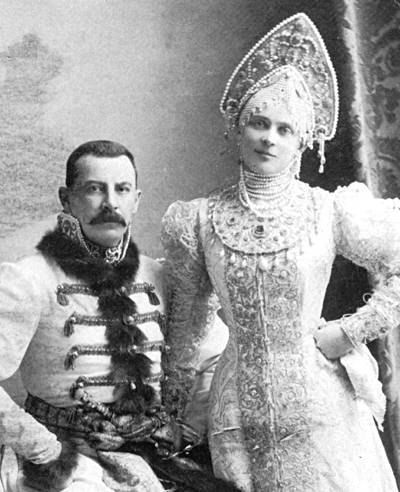

Above: Felix's parents dressed for a fancy dress ball at the Winter Palace in 1903.

My brother and I were left behind at Arkhangelskoye, for we were considered too young to take part in these festivities. But we were allowed to go to Moscow for the coronation. I have only to close my eyes now to see once more the brilliantly illuminated Kremlin, its red and green roofs and golden cupolas.

On the morning of the coronation, we watched the procession leave the Imperial Palace for the Ouspensky Cathedral. After the ceremony, the Tsar and the two Tsarinas wearing their coronation robes and crowns, followed by the Imperial family and all the foreign princes, left the cathedral to return to the palace. The sun was particularly bright that day, and played on the gold and gems of the glittering costumes. Such a sight could be seen only in Russia. When the Tsar and the two Tsarinas appeared before their people, they were verily the Lord's anointed. Who could then have foreseen that twenty-two years later nothing would remain of all this majesty and splendor?

It is said that while dressing the Tsarina for the ceremony one of her women pricked her finger on the clasp of the Imperial cloak, and that a drop of blood fell on the ermine...

Three days later, the dreadful Khodinka tragedy plunged the whole of Russia into mourning. Many considered this a bad omen for the dawning reign.* Most of the receptions planned to follow the coronation were canceled. However, on the bad advice of some of his counselors, Nicholas II decided to attend a ball given that evening at the French Embassy. There was deep dissension between the Grand Dukes. The three brothers of the Grand Duke Serge, then Governor General of Moscow, wanted to minimize the importance of a catastrophe for which he was to some extent responsible; they claimed that the program of coronation festivities should go on as arranged. The four "Mikhailovichi" (my future father-in-law, the Grand Duke Alexander and his brothers) firmly opposed this point of view, and for this were accused of conspiring against their elders.

NOTE* Through lack of organizatlon, during a distribution of the Tsar's gifts to the people, a terrible stampede took place and thousands of persons were trampled to death. ed to death.

After the coronation, my parents returned to Arkhangelskoye with their guests, including Prince Ferdinand of Rumania and Princess Marie. Prince Ferdinand was the nephew of King Carol I. I remember King Carol perfectly, for he often came to see my mother. He was handsome and had a kingly look, with hair turning gray and the features of an eagle. It was said that he cared only for politics and money, and neglected his wife, the Princess of Wied, who was well known as a writer under the pen name of Carmen Sylva. As they had no children, Prince Ferdinand was heir to the throne. He was an attractive man, but devoid of personality, extremely timid and undecided in both public and private life. He would have been rather a handsome man had his ears not stuck out, which spoiled his looks. He had married Princess Marie of Great Britain, the eldest daughter of the Duchess of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, sister of the Emperor Alexander III.

Left: felix as a young man.

Left: felix as a young man.

Princess Marie was already famous for her beauty: she had wonderful eyes of such a rare shade of grayish blue that it was impossible to forget them. Her figure was tall and slender as a young poplar, and she bewitched me so completely that I followed her about like a shadow. I spent sleepless nights conjuring up her lovely face. Once, she kissed me; I was so happy that I refused to let my face be washed that night. She was much amused to hear about this act of boyish infatuation, and many years later when I met her again at a dinner given in London at the Austrian Embassy, she reminded me of the incident.

It was at the time of the coronation that I witnessed a scene which deeply impressed my childish imagination. One day as we sat at a table, a noise was heard in the adjoining room. The door opened, and a very handsome young man on horseback rode in. He carried a bunch of roses which he threw at my mother's feet. It was Prince Gritzko Wittgenstein,an officer of the Tsar's escort a most attractive man, well known for his extravagances and doted on by women old and young. My father was furious at the young officer's audacity, and forbade him to enter his house again.

I could not understand my father's anger. I was indignant that he should have insulted a man who, in my eyes, was a hero, the reincarnation of the knights of yore, a cavalier who fearlessly declared his love by such a noble gesture!

For questions or comments about this online book contact Bob Atchison.