I go abroad - The Solovetz Monastery - Paris - The Duchess of Mecklenburg-Schwerin.

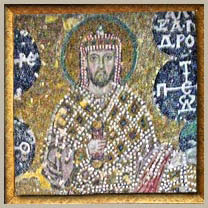

Left: Grand Duchess Elizabeth.

Left: Grand Duchess Elizabeth.

In 1913, Russia celebrated with great pomp the tercentenary of the Romanov dynasty. I went abroad at the beginning of the summer. Irina and her parents had to remain in Russia for the festivities, but joined me later in England.. After a brief stay in London, they spent the rest of the season at Le Treport, in France. I stayed with them for some time before returning to Russia.

Shortly after my return, the Grand Duchess Elisabeth invited me to go with her on a pilgrimage to the Solovetz Monastery. This monastery was founded in the beginning of the fifteenth century by St. Zavvati and St. Zosima, and is situated in the extreme north of Russia, on an island in the White Sea. We were to sail from Archangel, and as the Grand Duchess wished to visit some churches it was agreed that I should meet her at the ship. However, I lost all sense of time as I strolled about the town and reached the quay to find that the ship had left. I chartered a motorboat, but only caught up with the ship as it reached Solovetz, where I landed at the same time as the Grand Duchess, feeling very sheepish.

The entire community, headed by its superior, came to meet the Grand Duchess, and we were immediately surrounded by a swarm of monks, who stared at us with much curiosity. The monastery had beautiful crenelated fifteenth-century walls made from oval blocks of red and gray granite, and surmounted by numerous bell turrets. The surrounding country was extremely beautiful; countless lakes linked by canals turned the island into a sort of archipelago on which grew great forests of fir trees.

Our cells were pleasant and clean; on the whitewashed walls hung numerous icons, and before each of them a night light flickered. The food, on the other hand, was atrocious; during the whole of our stay, which lasted two weeks, we lived on holy bread and tea.

Most of the monks had long hair and beards. Some of them were filthy and unkempt; I have often wondered why uncleanliness seems to be the rule in most monasteries, as though it were necessary to smell bad to please God.

Right: Felix in fancy-dress costume.

Right: Felix in fancy-dress costume.

The Grand Duchess attended all the services. So did I at first, but after a couple of days I felt so holy that I begged to be excused from further attendance as I bad no intention of becoming a monk. But one of the services I attended made a deep impression on me owing to four anchorites who were there. Their hoods were pulled over their faces, giving only a glimpse of their emaciated features. Crossbones and skulls embroidered in white on their black frocks were particularly gruesome.

We went one day to visit one of these hermits, who lived in a cavern in the heart of the forest. It was reached through an underground passage so small that it could only be entered by crawling on all fours. I managed to take a snapshot of the Grand Duchess in this position, which I showed her to her great amusement. Our anchorite slept on a stone, and the sole ornament of his cell was an icon of Our Saviour before which a night light flickered, He gave us his blessing without saying a single word.

I spent a great part of my days going from one island to the other, often accompanied by young monks who sang in chorus; at twilight their fine voices, echoing over the water, were very moving. Sometimes I went alone, landing at any place I liked the look of. When I returned to the monastery, I joined the Grand Duchess and a few monks with whom I had made friends, and we had long talks together. Once back in my cell, I would remain for hours at a time before the open window, gazing at the immensity of the night sky. In the silence of the night, the beauty and mystery of nature seemed to draw me closer to the Creator. My prayers were wordless, but my heart was lifted up toward Him in simple trust.

He is everywhere, I thought, in everything that lives and breathes. Invisible, inconceivable. He is the alpha and omega of all things, the Infinite and the Truth.

In the past, I had been worried by many questions to which I could find no answer; I was tortured by the mystery of life. Very often, in the midst of the luxury that surrounded me, I bad felt its vanity and emptiness. Human misery, as I had seen it in the slums of St. Petersburg, filled me with horror. The philosophers whose books I had read had, for the most part, greatly disappointed me. Their theories sometimes seemed to me dangerous. Speculation such as theirs often ends by drying up the heart. I had an intense and instinctive dislike for destructive theories, and could not understand the stubborn pride of those who refused to accept with simple faith the things that were beyond their comprehension. On the other hand, the teachings of the Church had not enlightened me. To my mind, even the Holy Scriptures savored too much of man.

As I gazed out of the window of my cell into the starry night I found a peace that no theories had ever brought me. I even came to wonder whether monastic life was not the only true one. Yet had God himself not shown me the path that I should follow? When I spoke about this to the Grand Duchess, she replied without hesitation that I should marry the woman I loved and who loved me. "You will remain in the world and of the world," she said, "and wherever you go, you must always try to love and help your neighbor. Let yourself be guided by the only true teaching, that of Christ. It answers to all that is best in the heart of man and kindles the flame of Charity, which is Love."

The whole of my life has been the brighter for the radiance cast over it by this remarkable woman, whom I have regarded as a saint since my early youth.

On our return, we stopped again at Archangel. While the Grand Duchess visited churches and convents, I spent two hours before the train left in strolling around the town. In the main street my attention was attracted to a poster announcing the sale by auction of a white bear. I went into the auction room and bought the bear, which was as vicious as it was big. I could imagine the reception he would give intruders in the courtyard of our house on the Moika. I gave instructions that he should be sent at once to the station, and saw to it myself that he was put in a cattle truck which the terrified stationmaster promised to have coupled to the Grand Duchess' train. Having made these arrangements, I joined the latter in her saloon carriage where she was having tea with a few ecclesiastics who had come to see her off. All of a sudden, we heard furious grunts outside. A crowd gathered on the platform; our visitors exchanged anxious glances. The only person who kept calm was the Grand Duchess, and she was convulsed with laughter when she heard what it was all about. "You are quite mad," she said to me in English. "What will these poor bishops think?" I had no idea what they thought, but I knew what they would have liked to do to me from the sour looks they gave me and from their icy good-bys.

The train moved off to the cheers of the crowd, although no one knew whether their enthusiasm was for the Grand Duchess or the bear. We spent a very bad night, being awakened at each stop by bloodcurdling snarls. A large number of people, including court officials, awaited the Grand Duchess at St. Petersburg. One can imagine their stupefaction when they saw her return from a pilgrimage with a huge white bear!

In August, hearing that Irina had fallen and sprained her ankle very severely and that she had gone to see a doctor in Paris, I left immediately to join her. During her treatment, Which was long and painful, I went to see her every day at the Ritz Hotel where she was staying with her parents. My future father-in-law's sister, the Grand Duchess Anastasia Mikhailovna of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, was in town. Although she was well over forty, she had lost none of her high spirits; she was kind and affectionate, but her eccentric and despotic nature made her rather formidable. When she heard that I was going to marry her niece, she took me in hand. From that day my life was no longer my own. She was an early riser and she used to telephone me at eight in the morning. Sometimes she came to the Hotel du Rhin, where I was staying, and sat reading the papers in my room while I dressed. If I happened to be out, she sent her servants all over Paris to look for me and sometimes took part in the search herself. I never had a moment's peace. I had to lunch, dine, go to the theater and supper with her almost every day. She usually slept through the first act of a play, and then woke up with a start to declare that the performance was stupid and that she wished to go somewhere else. We often changed theaters two or three times in one evening. As she felt the cold, she made her footman sit on a chair at the door of her box, holding a small traveling bag filled with shawls, scarves and furs. All these objects were numbered. If by chance, she was awake and felt a draft, she would ask me to bring her such or such a number. I could have put up with all this but unfortunately she had a passion for dancing. At midnight, now wide awake, she would drag me to a night club where she danced till dawn.

Fortunately, toward the end of September, Irina had recovered and we all left for the Crimea.

A big thanks to Rob Moshein for scanning and correcting this text.

For questions or comments about this online book contact Bob Atchison.