My first trip to England - I return to Russia - I meet Rasputin - Departure for Oxford - Anna Pavlova - Life at the University - London society, fancy-dress balls, etc. - Farewell to Oxford Last few days in London - The English at home.

In London I stayed at the Carlton. Autumn had already set inthe wrong season for a first visit to England. However, my first impression was a very good one. I found the English attractive, hospitable, self-possessed and, above all, quite frankly imbued with a sense of their own superiority. The day after my arrival I lunched at the Russian Embassy and noticed with surprise that our ambassador, Count Benckendorff, hardly knew a word of Russian.

The next day I was asked to lunch with Prince and Princess Louis of Battenberg. The Princess questioned me at great length about Rasputin; all she had beard about his influence over her sister had alarmed her. She was too intelligent not to foresee the catastrophe that threatened my country. When I told her that I intended to enter an English university, she advised me to see her cousin, Princess Marie Louise of Schleswig-Holstein, and also the Bishop of London, as they might both be useful to me. I followed her advice at once. Both the Princess and the Bishop welcomed me most cordially and advised me strongly to go to Oxford. Later, when I was an undergraduate there, these two kindly counselors often came to visit me. The Bishop introduced me to a young Englishman, Eric Hamilton; we went up to Oxford together and studied at the same college. We have remained friends ever since, and he is now Dean of Windsor.

Taking my letters of introduction with me, I called on the master of University College, the oldest college in Oxford. The master received me most kindly and told me a great deal about the life and customs of the University. I learned that I would have a three weeks' holiday every two months, and that the summer vacations lasted three months; this would allow me to go to Russia quite often. The master showed me through the college and undergraduates' rooms, which were small but fairly comfortably furnished. One suite on the ground floor was vacant; it consisted of a large room with a grilled window looking onto the street, and a tiny room next to it. The master told me that the large room was called the "Club," because, no matter who had it, the other undergraduates were in the habit of meeting there to drink their whisky. He also told me that in my first year I would have to live in the college, but that during the two following years I could rent a house or flat in the town. I asked him if I could have these two rooms next winter.

This matter satisfactorily settled, I strolled through the town. Oxford, with all its ancient colleges surrounded by lovely gardens hidden behind high walls, won my heart. Innumerable generations of undergraduates had lived for centuries behind these ancient walls, a fit setting for the spirit of eternal youth. I would have hated to leave Oxford had I not been certain of returning.

Before returning home via Paris, I went to see the Grand Duke Michael Mikhailovitcb, the brother of my future father-in-law; he lived with his family at Kenwood, a lovely house on the outskirts of London. The Grand Duke had been in exile since his morganatic marriage to Countess Merenberg, Pushkin's granddaughter. She had been given the title of Countess Torby, and was a most delightful woman, very popular in London society. Her husband's cantankerous nature was a great trial to her; he never ceased thundering out abuse against his Russian family. Owing to his odd temperament, the Grand Duke could not be held responsible for his actions, but everyone was sorry for his wife. They had three children: a son they called "Boy" and two very pretty daughters, Zia and Nada. I saw a great deal of them during my years at Oxford.

I brought back from England quite a collection of animals for Archangelskoe: a bull, four cows, six pigs and a large number of roosters, hens and rabbits. The larger animals were sent direct to Dover to be shipped to Russia, but I took the crates containing the fowls and rabbits with me, and had them placed in the basement of the Carlton. I simply could not resist the temptation of opening the crates and letting the animals loose in the hotel. The result was marvelous! In the twinkling of an eye, they had scattered in all directions; cocks and hens fluttered and cackled, the rabbits messed the whole place up. What a pandemonium! The staff entered into the spirit of the thing and started to chase them all over the hotel, but the manager was furious and so were the guests. In short, it was a great success.

I stayed in Paris for a few days to see some friends, among them the musician Reynaldo Hahn and Francis de Croisset. We had several pleasant musical evenings together; Reynaldo was very fond of hearing me sing, and taught me some of his lovely songs.

I arrived in Russia in excellent spirits and full of energy. My parents were then at Tsarskoe-Selo. I found my mother much calmer and more resigned. The Grand Duke Dmitri was eager for a detailed description of my journey, and the Tsarina, who at that time was still on friendly terms with my mother and often came to see her, also questioned me about my stay in England and about her sister Princess Victoria. I refrained from telling her how anxious her sister was about Rasputin's influence on her! I soon left for Moscow, and resumed my visits to the hospital for tubercular cases. Many of the old patients had been replaced by others, but the staff remained the same, and I was happy to find myself among them once again. I often saw the Grand Duchess Elisabeth and had long talks with her. lks with her.

I spent the summer at Arkhangelskoe where I saw the animals I had bought in England. My father was delighted with my purchases and asked me to send for a second bull and three more cows. Accordingly I sent off the following telegram, which will give an idea of my knowledge of English: "Please send me one man cow and three Jersey women." The order was rightly interpreted, as the arrival of the animals testified, but a facetious journalist got hold of my telegram and it appeared in the English papers, to the joy of all my English friends.

This was 1909 and the year in which I met Rasputin for the first time.

We were back in St. Petersburg where I was spending Christmas with my parents before returning to England. For a long time I had been on friendly terms with the G. family, and more particularly with the youngest daughter, who was a fervent admirer of the starets. She was too innocent a girl to understand his ignominious nature, and too guileless to form an unbiased opinion as to his motives, He was, according to her, a man of exceptional spiritual power who had been sent into the world to purify and heal our souls, and to guide our thoughts and actions. This extravagant description left me skeptical, and although at that time I knew nothing definite about Rasputin something inside me made me suspicious of him. However, Mlle G.'s enthusiasm rouscd my curiosity and I questioned her in detail about the man she so much admired. She looked upon him as an apostle come straight from Heaven; he had no human weaknesses, no vices; he was an ascetic whose whole life was devoted to prayer. I heard so much about him that I felt I ought to judge him for myself, and I accepted an invitation to meet the starets a few days later at the G.s' house.

The G.s lived on the Winter Canal. When I entered the drawing room, mother and daughter were seated at the tea table, wearing the solemn expression of persons awaiting the arrival of a miraculous icon which was to bring a divine blessing on the house. In a little while the door opened and Rasputin came in with short quick steps. He walked up to me, said "Good evening, my dear boy," and attempted to kiss me. I drew back instinctively. He smiled maliciously and, going up to Mlle G. and then to her mother, he calmly put his arms around them and gave each of them a resounding kiss. From the very first his self-assurance irritated me, and there was something about him which disgusted me. He was of middle height, muscular and thin. His arms were disproportionately long, and just where his untidy crop of hair began to grow there was a great scar, which I found out later was the mark of a wound received during one of his highway robberies in Siberia. He seemed to be about forty, and with his caftan, baggy breeches and great top-boots he looked exactly what be was - a peasant. He had a low, common face framed by a shaggy beard, coarse features and a long nose, with small shifty gray eyes sunken under heavy eyebrows. The strangeness of his manner was disconcerting, and although he affected a free and easy demeanor one felt him to be ill at case and suspicious. He seemed to be constantly watching the person he was talking to.

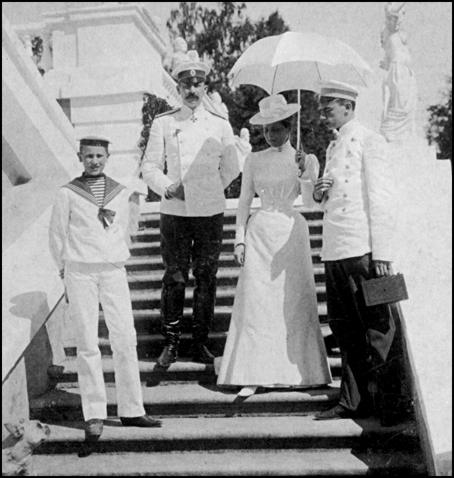

Right: Rasputin and two office4rs.

Right: Rasputin and two office4rs.

Rasputin remained seated for a few moments, then began to pace up and down the room with his short quick steps, mumbling under his breath. His voice sounded hollow, his pronunciation indistinct. We drank tea in silence as we watched him, Mlle G. with enthusiastic attention, I with great curiosity.

Soon he sat down and gave me a searching look. We began to talk. He spoke volubly in the tone of a preacher inspired from above, quoting the Old and New Testaments at random, often distorting their real meaning, which was a trifle confusing.

As he talked I studied his features closely. There was something really extraordinary about his peasant face. He was not in the least like a holy man; on the contrary he looked like a lascivious, malicious satyr. I was particularly struck by the revolting expression in his eyes, which were very small, set close together, and so deep-sunk in their sockets that at a distance they were invisible. But even at close quarters it was sometimes difficult to know whether they were open or shut, and the impression one had was that of being pierced with needles rather than of merely being looked at. His glance was both piercing and sullen; his sweet and insipid smile was almost as revolting as the expression of his eyes. There was something base in his unctuous countenance; something wicked, crafty and sensual. Mlle G. and her mother never took their eyes off him, and seemed to drink in every word he spoke.

After a little while Rasputin rose, and giving me a soft, hypocritical glance pointed to Mlle G. and said: "What a faithful friend you have in her! You should listen to her, she will be your spiritual spouse. Yes, she has spoken very well of you, and I too now see that both of you are good and well suited to each other. As for you, my dear boy, you will go far, very far."

With these words he left the room. When I went away, my mind was filled with the strange impression he had made on me.

A few days later I met Mlle G. again; she told me that Rasputin liked me very much and wanted to see me again.

Shortly after, I left for England where a very different life awaited me.

After an atrocious crossing, I spent the night in London. The manager of the Carlton, who had not forgotten my practical joke with the fowls, eyed me askance. I reached Oxford early the next morning and the first person I met was Eric Hamilton. He came with me to my rooms and promised to fetch me for lunch in the great dining hall, where I would see all my fellow undergraduates. Before lunch a manservant brought me my student's cap and gown. I liked the "togs," especially the mortarboard, but the luncheon was awful. Not that I minded, as I had other things to think about. In the afternoon I set about arranging my rooms. I turned the small one into a bedroom; my icons and their night light hanging in a corner over my bed reminded me of Russia. The large room became my living room. I placed my books on shelves, my knickknacks and photographs on tables, hired a piano, bought a few flowers and managed to make my rather cold and impersonal quarters look quite cosy and pleasant. That same evening, the "Club" was filled with undergraduates who sang, drank and chattered until dawn. Within a few days I know almost everyone in college. I was not a scholar; what interested me most was meeting people from different countries, talking to them and trying to understand their ideas, morals and customs, I could not have found a better place for this than Oxford, which was a meeting ground for the youth of all nations; I felt as though I were taking a trip around the world. I also liked the outdoor life there; not the violent games, but I got a lot of hunting, polo and swimming, which I enjoyed very much.

All the undergraduates who lived in the college had to be in by midnight, and this rule was very strictly applied. Anyone breaking it three times in one term was expelled. The culprit was always given a funeral; all the undergraduates escorted him to the station in a solemn procession, singing dirges. To help my friends, I had the idea of making a rope out of knotted sheets which could be attached to the roof and let down to the street. Anyone who was late had only to knock at my window and I immediately climbed up to the room and threw down the rope. One night, hearing a tap at the window, up I went, let down the rope and caught a policeman!

Without the personal intervention of the Bishop of London, I would certainly have been expelled.

I almost met the same fate on another occasion and on my own account. I was returning from London where I had dined with a fellow undergraduate. In spite of a heavy fog, we were driving at top speed, and we were anxious to be on time as I had already been late twice during the term, and a third offense would have automatically led to my expulsion.

Blinded by the fog, my friend who was driving crashed into the closed gates of a level crossing. The violent collision smashed the gate and I was thrown on the track. I must have lost consciousness, and, as I came to, I saw a light through the fog which grew larger and larger at terrifying speed. I was still too dizzy to realize what was happening, and was only saved by instinctively turning and rolling off the track. The London express thundered by, and the blast sent me bead over heels into the ditch. I picked myself up without a scratch, but my friend, though alive, was in very bad shape, with several broken limbs. As to the car, needless to say very little of it remained after the express had gone by. I telephoned from the gatekeeper's cottage for an ambulance, and after taking my friend to the Oxford Hospital I reached my college two hours late. However, in view of the circumstances, I was not expelled.

Every morning, after a cold shower which I hated, and a hearty breakfast, the only decent meal of the day, I attended lectures until lunchtime. The afternoon was given up to sports, and after tea each of us worked in his rooms. We spent the evenings at the "Club." Sometimes we had music, and there was always much conversation and lots of whiskey.

In this pleasant and healthy atmosphere I spent my first year at Oxford, but I suffered terribly from the cold. There was no means of heating my bedroom, and its temperature was much the same as out of doors. Water froze in my washbasin, and when I rose in the morning the carpet was so damp that I felt as though I were walking through a marsh.

The following year, availing myself of the right accorded to second-year men to live outside college, I rented a very ordinary and unattractive little house in the town, which I quickly furnished to suit me. Two of my fellow undergraduates, Jacques de Beistegui and Luigi Franchetti, came to live with me. The latter played the piano beautifully and we loved to listen to him till all hours of the night. I had brought a good chef from Russia. The rest of my staff was composed of a French chauffeur, an excellent English valet, Arthur Keeping, a housekeeper, and her husband who looked after my three horses. I had bought a hunter and two polo ponies; a bulldog and a macaw completed my menagerie. Mary, the macaw, was blue, yellow and red; the bulldog answered to the name of Punch. Like all of his kind, he was most eccentric, I soon noticed that checks on linoleum or on any kind of material drove him wild.

One day when I was at Davies my tailor's, a very smartly dressed old gentleman, wearing a checked suit, came in. Before I could stop him, Punch rushed at him and tore a huge piece out of his trousers. On another occasion I went with a friend to her furrier's; Punch noticed a sable muff encircled by a black and white checked scarf. He immediately seized it and rushed out of the shop with it. I, and everyone else at the furrier's, ran after him halfway down Bond Street, and it was only with the greatest difficulty that we managed to catch him and retrieve the muff, happily almost intact. When the holidays came, I took Punch to Russia, not thinking of the stringent law governing the entry of dogs into England. As six months in quarantine was out of the question, I decided to evade the law. On my way to Oxford in the autumn, I passed through Paris and went to see an old Russian ex-cocotte whom I knew. I asked her to come to London with me; she would have to dress as a nurse and carry Punch, disguised as a baby. The old lady agreed at once, as the idea amused her immensely, although at the same time it frightened her to death. The next day, we left for London after giving "Baby" a sleeping draught so as to keep him quiet during the journey, Everything went smoothly and not a soul suspected the fraud.

During one of my holidays in Russia I had the opportunity of seeing a most impressive sight: the glorification of the relics of Blessed Yossaf, which took place at the Kremlin in the Cathedral of the Assumption. The Grand Duchess Elisabeth had asked me to go with her, and the seats which had been reserved for her gave us an excellent view of the ceremony. A vast crowd filled the cathedral. The shrine containing the remains of the Blessed Yossaf was placed in front of the chancel, and sick people carried on stretchers, or in the arms of relations, were brought to kiss the relics. Cases of people "possessed by the Devil" were particularly gruesome; the inhuman screams and contortions of the victims grew more and more violent as they approached the shrine, and it sometimes took several people to hold them. Their shrieks drowned the magnificent religious chants as though Satan himself were blaspheming through their mouths; but their cries calmed down the moment they were made to touch the shrine. I saw several miraculous cures.

On September 14, 1911, Prime Minister Stolypin was assassinated at Kiev. He was a great statesman, deeply devoted to his country and to the throne.. He was a bitter enemy of Rasputin and never ceased to oppose him, thus earning the antagonism of the Tsarina, for she considered that an enemy of the starets must also be an enemy of the Tsar.

The attempt on Stolypin's life in 1906 had already been mentioned in a previous chapter. He had restored order in Russia by a series of wise measures. At the time of his death be was preparing a new law for the expansion of peasant land-ownership and the suppression of communal village property. He was killed by a revolver shot, during a gala performance at which the Tsar was present. As Stolypin lay dying on the ground, he raised himself in a last effort and, turning toward the Imperial box, made a gesture as though to bless its occupants. The assassin was a revolutionary Jew by the name of Bagroff who, strange as it may seem, worked in the Secret Service and was a friend of Rasputin's, An investigation was started but was quickly stopped, as though for fear of embarrassing disclosures. Stolypin's death was a triumph for the enemies of Russia and and of the throne; there was no one now to stand in the way of their criminal plans. Dmitri told me how indignant he was at the Emperor's indifference; both he and the Empress seemed to be quite unconscious of the seriousness of what had happened. The Tsarina made this curious remark to Dmitri: "Those who have offended God in the person of our friend, may no longer count on divine protection. Only the prayers of the 'starets,' which go straight to Heaven, have the power to protect them."

I spent some time in Paris toward the end of the holidays; I saw Jacques de Beistegui again, and we had a very good time before returning to Oxford. The Bal des Quat'z Arts was about to take place. I had heard so much about it that I was most anxious to see it, and Beistegui and I decided we would go. The question of costumes was simplified by the fact that prehistoric dress was de rigueur that year. A leopard skin was all that was needed. Beistegui, who never liked to waste money, bought an imitation skin and rigged himself out in a blond wig with two braids, which made him look more like a valkyrie than a cavedweller. As for myself, Diaghilev lent me the costume worn by Nijinsky in Daphnis et Chloe: a leopard skin and the big straw hat worn by Arcadian shepherds, tied round the neck and hanging over the shoulders.

The ball was a great disappointment. Never in my life have I seen anything so disgusting. A crowd of half-naked people rushing about excitedly in an overheated atmosphere heavy with the odor of perspiring bodies. Nakedness, which can be so chaste when associated with youth and beauty, is obscene in the old and the ugly. Most of the people at the ball were hideous, and all of them were drunk; they had lost all sense of decency and gave free play to their bestiality. Sickened by this revolting spectacle, we left early. Our leopard skins had been torn from us; nothing remained of our costumes but Jacques's blond wig and my Arcadian hat.

It was about this time that I met the famous demi-mondaine, Emilienne d'Alenqon, who was as lovely as she was intelligent. She had a subtle, caustic wit which was most entertaining, and I became a frequent guest at her fine house in the Avenue Victor Hugo. In her garden was a Chinese pavilion which she had furrushed and decorated with the greatest taste. Subdued lighting added to the voluptuous charm of a retreat where she spent most of her time reading, smoking opium, and composing poems which she was fond of reading to me. She was clever enough to surround herself with interesting people, and entertained admirably, always with the most perfect poise which, indeed, was characteristic of most of the great demi-mondaines of the period. Their distinction of mind and manner might well serve as a model to many so-called society women of today.

Apart from my regular holidays, a telegram sometimes summoned me to my mother, for her health was still very precarious. She had a particularly violent attack of nerves during a stay in Berlin with my father, and he, knowing that I alone could soothe her, sent for me and I came at once.

Although the heat in Berlin was stifling, I found my mother in bed, buried under furs, windows closed, and refusing all nourishment. She was in great pain and her cries were heartbreaking.

We had long known that there was nothing organic the matter with her and that her sufferings were purely nervous, so we sent for a psychiatrist, one of the greatest specialists in Berlin. As soon as he arrived I took him to my mother's room and let them alone together.

Suddenly a peal of laughter was heard through the door. It was so long since I had heard my mother laugh that I was dumbfounded. I opened her door: there was no mistake, it was my mother's charming, infectious laughter. Professor X sat stiffly on his chair looking very embarrassed, and obviously disconcerted by his patient's gaiety.

"Please take him away," she said as soon as I went in. "I can't bear it, he'll make me die of laughter!"

I showed the bewildered professor to the door. When I went back to my mother's room, she gave me no time to ask questions.

"Your precious professor is in far worse shape than I am," she said. "He looked at the watch by my bed, and seeing that it had stopped, what do you think he said? 'How curious! Have you noticed that your watch has stopped at the very hour when Frederick the Great died?"

All things considered, this eminent practitioner's visit was not without value, but he had certainly never expected to cure his patient by appealing to her sense of humor, even if unconsciously.

When I went away a few days later my mother was much better. A curious incident, which has remained unexplained, marked my brief visit; every night, when I went to bed, I found a red rose on my pillow. As no one could enter my room without a key, I was forced to conclude that one of the maids in the hotel had a soft spot in her heart for me!

Shortly after my return to England, I received an invitation to a big fancy-dress ball at the Albert Hall. As I had plenty of time, and I was in Russia on a holiday, I ordered a Russian costume in St. Petersburg. I had found some sixteenth-century gold brocade embroidered with red flowers, and the costume was magnificent: studded with precious stones, edged with sable, with a toque to match. It caused a sensation. I met all London at the ball, and the next day my photograph was in every paper. It was there that I met Jack Gordon, a young Scotsman, an Oxford undergraduate like myself, but at another college. He was extremely goodlooking and rather like a Hindu prince, and was very popular in London society. As we both liked to lead a gay social life, we rented two connecting flats at 4 Curzon Street. I engaged the Misses Frith, two most pleasant elderly spinsters who looked as if they had stepped out of one of Dickens' novels, to decorate them. All went well until I ordered a black carpet. They must have thought me the devil in person for, from that day, whenever I entered their shop, they disappeared behind a screen, and nothing could be seen of them but two quivering little lace caps. My carpet set a fashion in London-it even became the cause of a divorce. An Englishwoman ordered one against her husband's wish. He considered it funereal: "Either me or the carpet," he said, which was rash, for she chose the carpet.

One afternoon I had a telephone call from a well-known hostess asking me if I would preside at a big dinner she was giving at the Ritz. I accepted, and did my best to help her to receive her guests, who were the cream of London society. The fare was excellent, the wines were choice and the surroundings delightful. In fact, it was all a great success. Next day, to my intense surprise I received the bill, which amounted to a fabulous sum!

Left: Annna Pavlova.

Left: Annna Pavlova.

Diaghilev was then in town with the Russian ballet; Pavlova, Karsavina and Nijinsky were having a triumphant season at Covent Garden. I knew most of these artists, but I was particularly fond of Anna Pavlova. I had seen her in St. Petersburg, but I was then too young really to appreciate her. When I saw her in London in The Swan, she moved me profoundly. I forgot Oxford, my studies and my friends. Night and day, I could think of nothing but the ethereal being who held whole audiences under her spell, fascinated by the quivering of the swan's snow-white feathers on which a huge ruby blazed like a great drop of blood. In my eyes, Anna Pavlova was not just a great artist and as beautiful as an angel: she brought the world a message from Heaven! She lived in Hampstead at Ivy House, a charming place, and I often went to see her there. She had a genius for friendship, which she rightly held to be the noblest of all sentiments. She gave me more than one proof of this during the years when I was lucky enough to see her often. She knew me inside out: "You have God in one eye and the devil in the other," she used to say to me sometimes.

A delegation of Oxford undergraduates asked her to dance in the University theater. As she was going on tour, she had not a single free evening and at first she refused; but on learning that the students were friends of mine she agreed, thereby throwing her impresario into a panic. On the day of the performance she came to my rooms with the entire corp de ballet. As she wanted to rest, I left her there and took her company around Oxford.

When we returned from our walk, a car belonging to the parents of a girl whom certain misinformed persons alleged to be my fiancee was standing at my door. I met the whole family corning down the stairs, looking most embarrassed: not finding me in the drawing room, they had opened my bedroom door and seen Anna Pavlova asleep on my bed.

That evening Pavlova received a delirious ovation from Oxford's undergraduates.

It was about this time that what I took to be eye trouble, but turned out to be something quite different, first made its appearance. In theaters, drawing rooms, in the street, people suddenly seemed to be enveloped in a cloud. After this had happened several times, I consulted an oculist. He examined me very thoroughly and then assured me that there was nothing wrong with my eyesight. I stopped worrying about this phenomenon until the day when it took on a new and terrible meaning for me.

We rode to hounds once a week, and my friends used to come and have breakfast with me before going to the meet. It was during one of these meets that I first had a sinister foreboding when I saw this curious cloud creep over one of my friends who was sitting opposite me. A few hours later, on jumping a hurdle, he fell and was so severely injured that his life hung in the balance for several days.

Shortly afterward, a friend of my parents who was passing through Oxford came to lunch with me. During the meal, I suddenly saw him through the cloud. In writing to my mother, I mentioned this, adding that I was convinced that some danger threatened our friend. A few days later, a letter from her announced his death

When I happened to meet an occultist at a friend's house in London, I told him the story. He said that he was not surprised, that it was a form of second sight, and that he had heard of several similar cases, notably in Scotland.

For a whole year, I lived in dread lest this horrible cloud should hide the face of someone I loved. Fortunately these visions ended as suddenly as they had begun.

London society was split into several sets. I preferred the more unconventional ones, where I could meet artists and where a certain amount of informality was permitted. The Duchess of Rutland was the leader of one such set, She had a son and three daughters; I was particularly friendly with two of the latter, Margery and Diana. One was dark, the other fair; both were lovely, witty and full of imagination. It would be hard to say which was the more attractive of the two; I was under the spell of both. Lady Ripon, a celebrated beauty of the Edwardian era, was a woman of great breeding, and still very attractive in a very English way. Extremely intelligent, shrewd and astute, she could carry on a brilliant conversation on topics which she knew nothing about. Her sparkling wit had sometimes a touch of malice, concealed under her deceptively angelic air of innocence. She entertained a great deal at Coomb Court, her magnificent house near London, and she possessed the unique gift of giving her receptions the right atmosphere. The King and Queen were received with pomp and ceremony; politicians and men of learning found themselves in a correct if rather solemn atmosphere, and artists in a vie de Boheme that was free from all vulgarity yet easy and unconventional. Lord Ripon was a racing man with little taste for society, and put in brief and infrequent appearances at his wife's receptions. Sometimes his head could be seen peering over a screen, behind which it almost immediately disappeared.

In spite of the disparity in our ages, Lady Ripon had a great liking for me; she often telephoned, asking me to help her with her receptions and week-end parties.

One day she had invited Queen Alexandra and several other members of the royal family to lunch, and arranged a party for the same evening at which Diaghilev, Nijinsky, Karsavina and the entire Russian ballet were to appear.. The weather was very fine and the Queen gave no signs of leaving. At five, tea was served; six o'clock, seven o'clock came and still the Queen did not go. For some unknown reason Lady Ripon did not wish the Queen to know that she was having the Russian ballet at her house that evening. She begged me to help her avoid a "collision"-a somewhat tricky task. So when Diaghilev and his artists arrived I took them straight to the ballroom where an array of bottles of champagne had been put on ice. I locked the door and entertained them until the Queen left-when we all staggered out.

Lady Ripon's daughter, Lady Juliet Duff, was very like her mother in many ways. She had the same charm and spontaneous kindliness that made her so popular with all her friends.

It was at Lady Ripon's that I met Adelina Patti, Melba, Puccini and countless other artists. I also met King Manuel of Portugal there, and we remained fast friends until his death.

Although I went on studying at Oxford, I became more and more absorbed in the amusing and frivolous life I led in London. My flat in Curzon Street was too small, and I rented a larger one overlooking Hyde Park. I took a great deal of trouble over the decoration of this flat, and the result was most satisfactory.

I kept Mary, my macaw, and several other birds in the entrance hall, which I furnished with plants and wicker chairs and tables. To the right of the hall was a white dining room decorated with blue Delft pottery; the carpet was black, the curtains of orange silk, the chairs were covered with toile de Jouy in the same shade as the pottery. The room was lit by a blue glass bowl hanging from the ceiling, and by silver candlesticks on the table with orange shades. This effect of double lighting was very becoming to women, and gave to their faces the delicate semi-transparency of porcelain. To the left of the hall was a large drawing room divided by a recess. It contained a grand piano and mahogany furniture covered with chintz of a Chinese design in the same shade of green as the walls. On these I hung English colored prints. A white bearskin was stretched on the black carpet in front of the fireplace. The room was lit entirely by table lamps.

Next door was a smaller drawing room; it was modern, the color scheme green and blue, the furniture by Martine.

The walls of my bedroom were hung in two shades of gray cretonne, and blue curtains formed a sort of alcove; my icons were placed on either side of the bed in glass cases, and were dimly lit by night lights. The furniture was lacquered gray, and the carpet was black with a design of flowers.

My third year at Oxford was almost up, and I had to abandon my frivolous life for a few months to prepare for the final examinations. How I succeeded in passing them is still a mystery to me.

I was very sorry to leave Oxford and all my friends, and I felt quite melancholy when I got into my car, with my parrot and my bulldog, and set out for London.

I had taken such a fancy to life in England that I decided to prolong my stay there until the following autumn. Two of my cousins, Maya Koutouzoff and Irina Rodzianko, came to stay with me. Both were very beautiful women and I enjoyed going about with them.

For a performance at Covent Garden they wore, at my suggestion, tulle turbans with a big bow which made a perfect frame for their lovely faces. The whole audience stood up to stare at them, and during the interval all my friends flocked to our box, asking to be introduced. A handsome young Italian diplomat, known as "Bambino," instantly fell in love with Maya. He never left us from that moment, spent all his time at my flat, and had himself invited wherever we went.. He continued coming round to the flat after my cousins left, and we remained excellent friends.

Prince Paul Karageorgeviteb, later Regent of Yugoslavia, was then in London and stayed with me for some time. He was a very pleasant fellow, a good musician and excellent company. He, King Manuel, Prince Serge Obolensky, Jack Gordon and I were inseparable and went everywhere together.

I was asked to take part in a charity performance organized at Earls Court. This included a pantomime in which ambassadors from various countries were to make a formal entre'e before the queen of an imaginary country. The period chosen was the sixteentb century, and the beautiful Lady Curzon, seated on a throne and surrounded by courtiers, was to be the queen.... I was to impersonate a Russian ambassador from the Court of Moscow and made my entrance on horseback, followed by a retinue. My Russian costume was exactly right for the part, and a circus supplied a magnificent full-blooded, snow-white Arab horse. The first entrance was that of Prince Christopher, dressed as a king, his ermine-lined mantle trailing on the ground, a crown on his head and ... a monocle! I came next. To my astonishment, as I entered the ring, my horse on hearing the music began to dance. Everyone thought this was part of the program and when my horse had finished his act I was greeted with loud applause. But was I embarrassed! After the performance a number of friends had supper with me. Prince Christopher draped in his royal mantle, crown on head and monocle in eye, sat astride the hood of my car as I drove home, to the delight of the crowd. We drank so much that night that not one of my guests was in a fit condition to go home. The next day at about twelve o'clock I was awakened by the arrival of a chamberlain of the Greek Court in search of his Prince. He had looked everywhere for him, and had even sent an SOS to Scotland Yard. He searched among the bodies lying in armchairs, on sofas and even on the floor, but there was no Prince Christopher. I was becoming quite alarmed, when I suddenly heard snores which seemed to come from out of the piano. I lifted the silk cover and there was the Prince, rolled in his royal mantle, his crown by his side, his eyeglass in his eye, sound asleep.

My last year in London was the gayest of all. Fancy-dress balls were the rage and there was one almost every night. I had a wide range of costumes but my Russian one was always the greatest success.

I was to be Louis XIV at a ball given at the Albert Hall, and even went to Paris to have my outfit made. But, at the last minute, the costume struck me as being altogether too ostentatious, so I passed it on to the Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, and attended the ball, not as the King of France, but as the humblest of his subjects, a simple French sailor. The German prince looked magnificent: gold brocade, precious stories and feathers galore.

I was on very friendly terms with dear old Mrs. Hwfa Williams. "Madame," as we all called her, was almost completely deaf; but in spite of this and of her age, she was full of joie de vivre and was as popular as many younger and prettier women. King Edward VII took her with him wherever he went; she amused him so much that he could not do without her. Her country house, Coomb Spring, was named after a fountain to which Mrs. Williams attributed rejuvenating powers; she used to bottle the water from the so-called Fountain of Youth and sell it to her friends for fabulous sums. Week-ends at her house were always extremely gay. Her friends were all free-and-easy, and sometimes a trifle questionable. They would turn up unexpectedly, and were always sure of a warm welcome at any time of the day or night, or might even find her ready to set off with them for an evening jaunt to London. Once I spent a few days in Jersey and, as I was always interested in livestock, I stopped by a meadow to admire a magnificent herd of cows, One cow came up to my car, and looked at me so touchingly with her great eyes, that I was seized with an irresistible desire to buy her. Her owner at first demurred, but ended by agreeing.

As soon as I reached London, I entrusted my cow to the care of "Madame," who welcomed her with enthusiasm. She put a ribbon and a bell around her neck and called her Felicita.

Felicita became as tame as a dog; she went walking with us, and all but followed us into the house. In the autumn, when the time came to me to return to Russia, I wanted to take my cow back with me to Arkhangelskoe. But "Madame" grew deafer and deafer. She couldn't hear a word I said. I wrote on a piece of paper: "The cow belongs to me." She tore the paper up under my nose, tossed the pieces in the air, and looked at me with a mocking smile. Faced by such treachery, I resolved to kidnap Felicita.

I got a few friends together, and one night we all drove to Coomb Spring wearing masks. Unfortunately the noise of the engine woke the lodgekeeper who, thinking we were gangsters, gave the alarm. "Madame" jumped from bed, seized a revolver and began firing at us from her window. It was impossible to make her hear or understand who we were. When all the servants had been roused by the uproar, she at last recognized us. The cunning old lady served us a magnificent supper, and such heady wines that we completely forgot what we had come for.

On the eve of my departure for Russia, I gave a big farewell party at the Berkeley. The dinner, which was in fancy dress, was followed by a ball at the studio of one of my friends, a painter. The next day I left London, taking with me the most wonderful and lasting memories of my life in England.

It is sometimes said on the Continent that England is everyone's enemy, and La perfide Albion is often blamed for her selfish and insular policy. For myself, having a horror of politics, I prefer to regard the English from another angle. I have known them in their own country: hospitable, great gentlemen and faithful friends. The three years that I spent among them were perhaps the happiest of my youth.

A big thanks to Rob Moshein for scanning and correcting this text.

For questions or comments about this online book contact Bob Atchison.