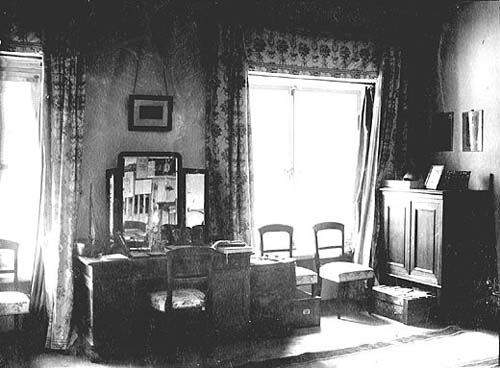

The Children's Floor - Aleksey's Bedroom

Bedroom of the Tragic Hemophiliac Tsarevich

"The heir's disease was a hard blow for the Tsar and the Tsarina. It won't be an exaggeration to say that her son's disease told badly on the Tsarina's health and she could never get rid of the feeling that she was responsible for her son's illness. The Tsar himself grew many years older in a year's time and people who were close to him could not but notice that his mind was never free from disturbing thoughts.I remember a beautiful angelic-looking child with golden hair and charming meaningful eyes. But the slightest injure caused bruises all over his body. The heir was very well looked after and guarded but it didn't always help as the child was very lively and when he hurt himself he cried the whole nights through.

I remember the Tsarina was always anxious when some important foreign visitor was expected - she tried hard to make Aleksey look a healthy child. At first they kept his disease secret as all hoped for his recovering. Once, just before the Kaiser was to arrive, the boy fell down in spite of all the precautions and got a big bruise on his forehead. Of course, the Kaiser understood at once what the matter was as his brother's (Prince Henry) two or three sons suffered of the same disease."

Earlier, in 1923 Anna Vyrubova wrote:

Alexei, the only son of the Emperor and Empress, a more tragic child than the last Dauphin of France, indeed one of the most tragic figures in history, was, apart from his terrible affliction, the loveliest and most and most attractive of the whole family. Because of his delicate health Alexei began life as a rather spoiled child. His chief nurse, Marie Vechniakova, a somewhat over-emotional woman, made the mistake of indulging the child in every whim. It is easy to understand why she did so, because nothing more heart-rending could be imagined than the little boy's moans and cries during his frequent illnesses. If he bumped his head or struck a hand or foot against a chair or table the usual result was a hideous blue swelling indicating a subcutaneous hemorrhage frightfully painful and often enduring for days or even weeks.At five Alexei was placed in charge of the sailor Derevenko, who for a long term of years remained his constant body servant and companion. Derevenko, while devoted to the boy, did not spoil him as his women nurses had done, and the man was so patient and resourceful that he often did wonders in alleviating the child's pain. I can still in memory hear the plaintive, suffering voice of Alexei begging the big sailor to "lift my arm," "put my leg up," "warm my hands," and I can see the patient, calm-eyed man working for hours on end to give the maximum of comfort to the little pain racked limbs.

As Alexei grew older his parents carefully explained to him the nature of his illness and impressed on him the necessity of avoiding falls and blows. But Alexei was a child of active mind, loving sports and outdoor play, and it was almost impossible for him to avoid the very things that brought him suffering. "Can't I have a bicycle?" he would beg his mother. "Alexei, you know you can't." "Mayn't I play tennis?" "Dear, you know you mustn't." Often these hard denials of the natural play impulse were followed by a gush of tears as the child cried out: "Why can other boys have everything and I nothing?"

Suffering and self-denial had their effect on the character of Alexei. Knowing what pain and sacrifice meant, he was extraordinarily sympathetic towards other sick people. His thoughtfulness of others was shown in his beautiful courtesy to women and girls and to his elders, and in his interest in the troubles of servants and dependents. It was a failing of the Emperor that even when he sympathized with the troubles of others he was rather slow to take action, unless indeed the matter was really serious. Alexei, on the contrary, was always for immediate action. I remember an instance when a boy in service at the palace was discharged for some reason which I have quite forgotten. The story somehow reached the ears of Alexei, who immediately took sides with the boy and gave his father no rest until the whole case was reviewed and the culprit was forgiven and restored to duty. Alexei usually defended all offenders, yet when the day came when his parents, in deep distress, told him that Father Gregori, that is, Rasputin, had been killed by members of his own family the boy's grief was swallowed up in rage and indignation. "Papa," he exclaimed, "is it possible that you will not punish them? The assassins of Stolypin were hanged."

I ask the reader to remember that the Imperial Family firmly believed that they owed much of Alexei's improving health to the prayers of Rasputin. Alexei himself believed it. Several years before Rasputin had assured the Empress that when the boy was twelve years old he would begin to improve and that by the time he was a man he would be entirely well. The undeniable fact is that after the age of twelve Alexei did begin very materially to improve. His illnesses became farther and farther apart and before 1917 his appearance had changed marvelously for the better. He resembled in no way the invalid sons of his mother's sister, Princess Henry of Prussia, who suffered from his own terrible malady. What the best physicians of Europe had been unable to do in their case some mysterious force had done in the case of the Tsarevich. His parents to whom the young boy was as their very heart's blood believed that the healing hand of God had wrought the cure, and that it was in answer to the supplication of one whose spirit was able to rise in higher flight than theirs or any other's. They knew of course that the boy was not yet entirely well, but they believed that he was getting well. Alexei believed this also and it is certain that he looked forward to a healthy, normal manhood.

Above: The opposite wall of Aleksey's bedroom.Bob Atchison

Imperial Bedroom

Imperial Bedroom Portrait Hall

Portrait Hall Mauve Room

Mauve Room Maple Room

Maple Room Aleksey's Bedroom

Aleksey's Bedroom Nicholas's Study

Nicholas's Study Aleksey's Playroom

Aleksey's Playroom Formal Reception

Formal Reception Balcony View

Balcony View Aleksey- Balcony

Aleksey- Balcony Children-Mauve

Children-Mauve Nicholas's Bathroom

Nicholas's Bathroom Alexandra- Mauve

Alexandra- Mauve Nicholas's Reception

Nicholas's Reception Tsarskoe Selo Map

Tsarskoe Selo Map