Moscow - Our life at Arkhangelskoye - Serov the painter - A supernatural adventure - Our neighbors in the country - Spaskoye-Selo.

I preferred Moscow to St. Petersburg. The Muscovites had escaped the influence of Western civilization and had remained essentially Russian; Moscow was the real capital of the Russia of the Tsars.

Families of the old aristocracy led the same simple, patriarchal existence in their fine town houses as they did in their summer residences in the country. Imbued with century-old traditions, they had little contact with St. Petersburg, which they considered too cosmopolitan.

The rich merchants, who were all of peasant origin, formed a class of their own. Their beautiful, spacious houses often contained extremely valuable collections. Many of these merchants still wore the Russian blouse, wide trousers and great top-boots, though their wives ordered their clothes from the best French dressmakers, wore the finest jewelry, and rivaled in elegance the great ladies of St. Petersburg.

The Muscovites kept open house. Visitors were taken straight to the dining room, where they found a table permanently laid with zakouskis and various kinds of vodka. No matter what the hour, one was obliged to eat and drink.

Most rich families had estates just outside the city, where they lived according to the time-honored customs of old Muscovy and practiced its traditional hospitality. Friends who had come there re

for a few days could just as well stay for the rest of their lives, and their children after them for several generations.

Like Janus, Moscow was double-faced: on one side was the holy city with its innumerable golden-domed, brightly painted churches; chapels where thousands of candles burned before icons; convents concealed behind high walls, and crowds of the faithful thronging all places of worship. On the other side was a gay, lively, noisy town bent on luxury and pleasure, and even profligacy. A motley crowd moved along the brightly-lit streets and, swift as arrows, the smart lihachis sped by with a jingle of bells. The lihachis were luxurious one-horse hackney carriages, extremely light and speedy, driven by well-dressed young coachmen who were not always unaware of the adventures on which their clients were setting out.

A mixture of piety and dissipation, of religion and self-indulgence, was characteristic of Moscow. The Muscovites reveled in the grosser forms of pleasure, but they prayed as much as they sinned.

Moscow was a great industrial center, and also very rich in intellectual and artistic resources.

The opera company and the ballet at the Grand Theater could compete with those of St. Petersburg. The Little Theater's repertory of drama and comedy was much the same as that of the Alexander Theater, and the acting was of the first order. One generation of artists after another maintained its high traditions. Toward the end of the last century, Stanislavsky created the Art Theater; be was a manager and producer of genius, and was greatly assisted by such men as Nemirovitch Danchenko and Gordon Craig. A surpassing gift for training actors enabled him to achieve a unique ensemble in which even the most insignificant parts were taken by first-class performers. There was nothing conventional in the stage scenery; it was the reflected image of life itself.

I was an enthusiastic and assiduous habitue of Moscow theaters. Often too, I went to hear the gypsies at the Yar and Strelna restaurants; they were far superior to those of St. Petersburg. The name of Varia Panina is remembered by all who had the good fortune to hear her sing. Even when she was well on in years, this very ugly woman, always dressed in black, cast a spell over her audience with her deep, pathetic voice. At the end of her life she married an army cadet of eighteen. On her deathbed, she asked her brother to accompany her on the guitar while she sang one of her greatest successes, "The Swan Song," and breathed her last on the final note.

Our Moscow house was built in 1551 by Tsar Ivan the Terrible. The Tsar used it as a hunting lodge, for it was then surrounded by forests. An underground passage connected it with the Kremlin. It was designed by Barna and Postnik, the architects to whom Moscow owes the celebrated church of St. Basil the Blessed. To make sure that they would never duplicate this wonderful building, Ivan the Terrible rewarded the architects by cutting off their tongues and arms and putting out their eyes. This pitiless monarch's fits of cruelty were always followed by remorse and penance; apart from his crimes he was an extremely intelligent man and a great statesman.

The Tsar never stayed long in this house; he used it for his fabulous entertainments, and then returned to the Kremlin through the underground passage. This labyrinth of galleries had several exits which allowed him to put in sudden appearances at places where be was least expected.

He owned a library which was unique of its kind and in order to preserve it from fire-then a very frequent danger - he had it walled into the underground passage. It is known, from historical evidence, that it is still there, but, as portions of the passage have caved in, all attempts to trace it have been in vain.

After the death of Ivan the Terrible the house remained empty for almost a century and a half; in 1729 Peter II gave it to Prince Gregory Yussupov.

During the restorations carried out by my parents at the close of the last century, one of the entrances to this passage was discovered. On going into it, they found a long gallery with rows of skeletons chained to the walls!

The house was painted in bright colors after the old Muscovite style. It stood between a formal courtyard and a garden. All the rooms were vaulted and decorated with frescoes. The largest room contained a collection of very fine gold and silver plate; the walls were bung with portraits of the Tsars in carved frames. The rest of the house was a network of innumerable small rooms, dark passages and diminutive staircases leading to secret dungeons. Thick carpets stifled every sound, and the silence added to the atmosphere of mystery which pervaded the house.

Everything in it conjured up the memory of the terrible Tsar. On the third floor, on the very spot where there is now a chapel, there used to be grilled niches containing skeletons. I thought that the souls of these poor creatures must haunt the place, and my childhood was obsessed by the terror of seeing the ghost of some murdered wretch.

We were not fond of this house, for its tragic past was too vivid, and we never stayed long in Moscow. When my father was made Governor General of the city we lived in a wing connected to the house by a winter garden. The house itself was used only for parties and receptions.

Certain Muscovites were most eccentric, and my father liked to surround himself with these oddities, and found them entertaining. Most of them belonged to various societies of which he was the honorary president: dog clubs, bird fanciers, associations and, in particular, a bee-keeping organization, all the members of which belonged to a widespread sect of castrates, the Skoptzis. One of these, old Mochalkin, who directed the organization, often came to see my father. He bad a soprano voice and the face of an old woman, and altogether his appearance rather frightened me. But it was quite another matter when my father took us to visit the beekeeping center. About a hundred Skoptzis gathered to greet us. We were given a delicious lunch followed by a very fine concert. All the performers were men with feminine voices; imagine a hundred old ladies dressed as men, singing popular songs with children's voices. It was at once touching, sad and rather funny.

Another strange person was a round, bald-headed little man called Alferoff. He had had a shady past as a pianist in a brothel and as a dealer in birds. In the exercise of this last calling, he got into trouble with the police for dyeing humble barnyard fowls in lively colors and palming them off as exotic birds.

He always showed us the deepest respect when he came to our house, even to the point of kneeling and remaining in that position until we entered the room. Once, when the servants bad forgotten to tell us he had called, be waited for one hour on his knees. During meals, he always rose when one of us addressed him and would not sit down until he bad answered. Engaging him in conversation became a pastime of which I never tired, and I never gave the poor man time to eat. When visiting us, he wore an old dress suit that had once been black but which time had changed to a dirty green; it was probably the suit in which he used to play dance music for ladies of easy virtue. His stiff collar was so high that it concealed part of his ears; round his neck hung a huge silver medal which bad been struck to commemorate the coronation of Nicholas II; his breast was covered with small medals, which were prizes he had won at bird shows for his so-called exotic specimens.

My father sometimes took us to see a parish priest in whose house a number of cages filled with nightingales hung from the ceiling. Our host set these birds singing by means of homemade instruments which be struck one against the other. He directed the singers like the leader of an orchestra, making them stop or start off again at will; he could even make each bird perform a solo. I have never heard anything like it since.

At Moscow, as at St. Petersburg, my parents kept open house. We knew a woman, a well-known miser, who contrived to be invited to meals in different houses every day of the week, except Saturdays. She would congratulate her hostess extravagantly on the excellence of the cooking and end by asking for anything that remained. Without even waiting for an answer, she called a servant and had the food put in her carriage. On Saturdays she invited her friends to her house to partake of a meal composed of a week's leftovers from their own tables.

Summer saw us back at Arkhangelskoye; we had many guests, and some of them stayed for the whole season.

My liking for them depended entirely on the degree of interest they took in our beloved estate. I bad a violent hatred for those who were indifferent to its beauties and merely came to eat, drink and play cards. To me their presence was a desecration. To escape from them I used to take refuge in the park, wandering among the groves and fountains, never tiring of a landscape where art and nature harmonized so perfectly. Its serenity brought me peace and quiet, and in its romantic setting my imagination had free play. I used to pretend I was my great-great-grandfather, Prince Nicholas, absolute monarch of Arkhangelskoye. I would go to our private theater and, seated in a box, would watch an imaginary performance in which the finest artists played, sang and danced for me. Sometimes I myself would go on the stage and sing, and be so carried away by my imagination that the ghosts of past audiences seemed to come to life and applaud me. When I awoke from my dreams, it was as though my personality had been split in two: one part of me jeering at such nonsense, the other grieving that the spell was broken.

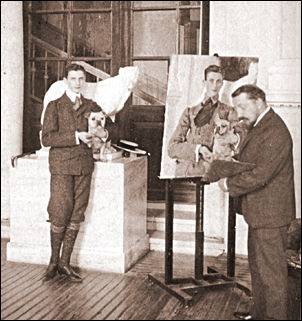

Left: Serov painting Felix.

Left: Serov painting Felix.

Arkhangelskoye had a friend and admirer after my own heart in the person of Serov, the artist who came to paint our portraits in 1904.

He was a delightful man. Of all the artists I have ever met in Russia or elsewhere, my memory of him is the most precious and vivid. His admiration for Arkhangelskoye, which revealed his acute sensibility, was the basis of our friendship. In an interval between sittings, we sometimes went into the park, sat down on a bench under the trees, and had long talks, His advanced ideas influenced the development of my mind considerably. I must add that in his opinion there would have been no cause for a Revolution if all rich people had been like my parents.

Serov bad a great respect for his art and never consented to paint a portrait unless the model interested him. He refused to paint a very fashionable lady of St. Petersburg whose face did not inspire him. However, be finally yielded to the lady's entreaties but, after the last sitting, he added to the portrait an enormous hat, which concealed three-quarters of her face. When the model protested, he replied that the hat was the most interesting part of the portrait.

He was too independent and too disinterested to conceal his feelings. He once told me that when he was painting the Tsar's portrait the Tsarina exasperated him by continual criticisms; so much so that one day, losing all patience, he banded her his palette and brushes and suggested that she should finish the work herself.

This portrait, the best ever painted of Nicholas II, was ripped to pieces during the 1917 Revolution, when a frenzied mob invaded the Winter Palace. An officer, who was a friend of mine, brought me a few shreds of it which I have reverently kept.

Serov was very much pleased with the portrait he painted of me. Diaghilev asked us to allow him to include it in the exhibition of Russian art which he organized in Venice in 1907, but it brought me so much notoriety that my parents were annoyed and requested Diaghilev to withdraw it from the exhibition.

Every Sunday after church my parents received the peasants and their families in the courtyard in front of the chateau. The children were given refreshments, and their parents presented their requests and grievances. These were always treated with great kindness and their requests were rarely refused.

Great popular festivals, in which singing and dancing by the peasants played an important part, took place in July. Everyone enjoyed these festivals; my brother and I were particularly enthusiastic and looked forward to them impatiently each year.

Our foreign guests were always surprised by the spirit of fraternity that existed between us and our peasants. This was the result of our straightforward dealings with them, and never made them less respectful to us. The painter Francois Flameng, who stayed with us at Arkhangelskoye, was particularly impressed by this. He was so delighted with his visit to us that he said to my mother, on taking leave: "Promise me, Princess, that when my artistic career is over you will allow me to become the honorary pig of Arkhangelskoye!"

One year, toward the end of the holidays, my brother and I had a strange experience, the mystery of which was never solved. We were leaving by the midnight train from Moscow to St. Petersburg. After dinner we said good-by to our parents and entered the sleigh which was to take us to Moscow. Our road led through a forest called the Silver Forest which stretched for miles without a single dwelling or sign of human life. It was a clear, lovely moonlight night. Suddenly in the heart of the forest, the horses reared, and to our stupefaction we saw a train pass silently between the trees. The coaches were brilliantly lit and we could distinguish the people seated in them. Our servants crossed themselves, and one of them exclaimed under his breath: "The powers of evil!" Nicholas and I were dumbfounded; no railroad crossed the forest and yet we had all seen the mysterious train glide by.

We had frequent contacts with Ilinskoe, the estate belonging to the Grand Duke Serge Alexandrovtch and the Grand Duchess Elisabeth Feodorovna. Their house was tastefully arranged in the style of an English country house: chintz-covered armchairs and a profusion of flowers. The Grand Duke's entourage lived in pavilions in the park.

It was at Ilinskoe, when I was still a child, that I met the Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich and his sister the Grand Duchess Marie Pavlovna, both of whom lived with their uncle and aunt. Their mother, Princess Alexandra of Greece, had died in their infancy and their father, the Grand Duke Paul Alexandrovich, had been obliged to leave Russia after his morganatic marriage to Mine Pistohlcors, later Princess Paley.

The Grand Duke's court was composed of the most heterogeneous elements; it was very gay and the most unexpected things happened there. One of its most diverting personalities was Princess Vassilchikov who was as tall as a drum major, weighed over four hundred pounds, and in her stentonian voice used the language of the guardroom. Nothing amused her more than to show off her muscular strength. Anyone passing within her reach risked being snatched up as easily as a newborn babe, to the joy of all present. The princess often chose my father for a victim, and he did not appreciate the joke in the least.

Prince and Princess Scherbatov were other neighbors of ours, who always welcomed their guests most graciously. Their daughter Marie, beautiful, intelligent and charming, later married Count Tchernicheff-Besobrasoff. She was always one of our most intimate friends, and neither age nor the misfortunes she has suffered have in any way affected her fine qualities.

Spaskoye-Selo, one of the oldest estates belonging to my family, was also near Moscow. Prince Nicholas Borissovich lived there before buying Arkhangelskoye.

I never knew why this estate had been abandoned and reduced to the sad neglect in which I found it when I visited the place in 1912. On the border of a forest of fir trees, a large palace embellished by a colonnade stood on a height; the building seemed to be in perfect harmony with the magnificent site. But, as I drew nearer, I was horrified to see that nothing was left of it but ruins! The doors and windows had disappeared; I picked my way through rubble, for the ceiling had caved in; here and there I discovered the remains of past glories: fine stucco ornamentation, paintings, or rather traces of paintings, in delicate colors. I passed through suites of rooms, each one more beautiful than the other, where stumps of marble columns lay on the ground like severed limbs; finely inlaid paneling of ebony, tulip or violetwood gave one an idea of what the decoration had once been.

The wind swept through the rooms, howling round the thick walls, rousing the echoes of the past, as though proclaiming itself the sole master of the ruined palace. I was seized with anguish; from the rafters, owls stared at me with their round eyes and seemed to say: "See what has become of your ancestral home."

I turned away with a heavy heart, thinking of the unpardonable errors which can be committed by those whose possessions are too great.

For questions or comments about this online book contact Bob Atchison.